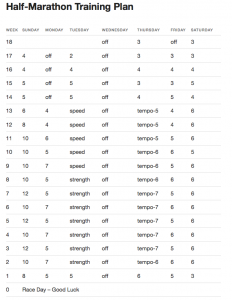

My original thought was to take the Hanson brothers running plan, which looks like this:

http://www.hansons-running.com/training-plans/half-marathon-training-plan/

and pretty much just replace each number each day with something piano related. Instead of increasing the distances, I would just increase the amount of practice time. My “race” would be a recital. I picked Brahms’ Violin Sonata no. 1, because I’m considering eventually doing a collaborative piano masters, and I’ve heard that that’s a typical audition piece, Chopin etude op. 10 no. 12, because in my modern dance accompanying I sit on a cajon and play it with my right hand while playing piano with my left hand, so developing a wide ranging, flexible, virtuosic left hand is going to be helpful, and some Bill Evans solo pieces (Very Early, I Got It Bad, maybe Waltz for Debby, and Blue In Green), because I’ve played them before, and they should contrast the rest of the program nicely.

I thought back to previous successful practice time and remembered that I’ve always liked 25 minute sections of time. I know that there’s research that pretty much says that your brain doesn’t work in a focused way for any longer than that. (I guess there’s a thing called the “Pomodoro Technique” that advocates this as well)

So I decided that I would do that with this plan. Also, at times I had difficulty fitting the longer runs into my daily schedule, and thought that if I had 25 minute chunks, it would be much simpler, even on a day when I had to practice for 2 hours, to get in 25 minutes here, an hour there, etc.

The running plan has what it calls “SOS” days (something of substance) on three days, and easy days the other three. It seems easy to design a harder workout, but a “harder” practice session is trickier. I’ll tackle that question in a separate post.

I came up with a list of possible 25 minute practice tasks, which are detailed after the plan. Feel free to skip those unless you’re particularly nerdy about piano practice techniques.

I basically plugged these in, trying to keep each day of the week consistent. This is the first four weeks, which, like in the running plan, are really not the meat of your work. They are designed to get your body, mind, and (very importantly for me) schedule used to consistent training.

After initially plugging them in, I chatted about this plan with a colleague and fellow pianist and runner (who is a better classical pianist than me, and ran ultra marathons instead of halfs, so, awesome reminder that You Are Not Special), I codified each day into categories, even if it doesn’t quite fit those SOS days, it is structured. Just maybe not correctly! Again, that’s another post. These categories are listed at the top of week 1.

I created the grid in Adobe InDesign and then made it into a “form” in Adobe Acrobat Pro. This way I can easily edit each box, while leaving the overall structure intact. The bad part is that, as far as I can figure, I can’t edit the overall structure without starting over and erasing all the “form” boxes, so I can’t correct the typo that says that I’m playing the Chopin Etude no. 2 instead of no. 12. Also, I should have made it more generic, so that I could reuse it in the future, or someone else (who maybe didn’t want Saturday as their off day) could use it. That will be a future project. If anyone is really good with those programs and has done something like this a lot, I’d love some advice.

Here goes! Starts tomorrow!

Practice tasks key:

Rhythms: Take any steady rhythm and change it so that one of the subdivisions is longer than the others. Go through every permutation. Triplets become eighth and two sixteenths, then sixteenth eighth sixteenth, then two sixteenths and an eighth. I’ve used this obsessively since Anthony Padilla showed it to me in one of my first lessons in college.

Slow: duh. Clear mapping of every motion and musical gesture. Play everything perfectly. Effortless Mastery style (great book).

Deep Stacatto: has been suggested as an important technique for learning the left hand of the Chopin etude.

Arpeggio work: pretty important for the Chopin.

Thumb exercises: related to arpeggios.

I don’t have a plan for this, but it has been suggested that I also may need some specific 4th finger strengthening exercises for the Chopin, because I’ll often be crossing to that finger and will need to pivot on it well.

Melody w/ roots: develop a melodic and harmonic understanding of the piece, keep the focus on melody. I’ve recently realized that I actually sight-read (actually, read generally) by basically creating an instant lead sheet in my brain and I sometimes play fast and loose with the details of the accompaniment texture. This works great while playing piano reductions of ballet music or musicals or even accompanying a choir. In the real world I sometimes think it’s more important not to play any wrong notes than to play all the right ones. Needless to say, this doesn’t really apply to Brahms…

Score study and memorization: patterns, clarity of interpretation.

Singing and playing: again something I have done obsessively since I worked on my first Bach fugue with Anthony Padilla. SATB texture. Sing S, play A. Sing S, play T. Sing S, play B. Sing S, play A+T. Sing S, play A+B. Sing S, play T+B. Sing S, play A,T+B. In Gary Chester’s “New Breed” for drummers he urges a shockingly similar approach to developing limb independence and control. It develops such great concentration and an ability to focus on multiple independent lines. I would love, as an accompanist, to be able to sing the entire Violin part to the Brahms while I played the piano part.

Recording

reviewing recordings

developing exercises for hard measures, based on recordings

Mental practice: I’m not sure I know what this is yet. Visualization and audiation could be a key. At some point in the process I definitely want to consistently do two exercises that I heard the great saxophone player and teacher Steven Jordheim talk about once and that I’ve never applied. One is to practice, in time, feeling the emotions that you want to be conveying through a piece. It seems almost like an acting technique. The second is to visualize and audiate through the entire recital start to finish, from walking onstage and bowing, to playing the first notes, right through, in real time, keeping your focus and concentration, and starting over if you lose the train.